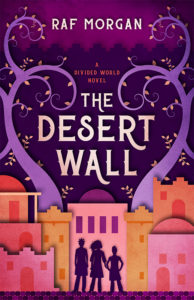

The Desert Wall

Book one of the Divided World series

Malenie found the perfect place to hide from the world.

No one else sees the endless Wall that stretches across the desert, and when Melanie is in the shadow of its magic, she becomes invisible. Bullies can’t torment her. Her ex-best friend can’t ignore her. And her beloved Papa doesn’t worry about the secret that puts her life in danger…

When a stranger comes to town and abducts Papa, Malenie is thrust into a dangerous quest to save him. She learns that the Wall holds secrets that will bring her in touch with her ancestral magic, bind her to new friends and old enemies, and force her to confront a deadly villain. To save Papa, she will have to learn to use the mysterious magic that is inscribed on her very skin.

The Desert Wall is the first book in a new series about friendship, families and magic.

Chapter One

Malenie was hiding. The sun burned hot and brilliant on the white plaster and dull adobe houses, banishing the shadows from even so narrow an alley. Sweat prickled along her hairline. She leaned against the wall, its grit rubbing off on her back, and tried to stop panting. Fear and humiliation made a hard fist of her stomach, urging her to run again. Only two streets over, the market hummed with activity, promising safety.

“I hate them,” she whispered, though she wanted to shout. After almost a moon without trouble she had been careless, and now here she was, with at least one bully somewhere behind her. But a cactus never has just one spine, and bullies never travel alone. She tucked her black hair behind her ears, pressed closer to the house and crept forward. She peeked around the corner, thinking, Please.

The boy was so close she smelled fennel and anise on his breath as they both recoiled. “Told you,” said the tall girl with him, stepping forward, forcing Malenie back into the alley. Malenie’s heartbeat seemed to shake her whole body, demanding that she fight or run. Run or fight. The boy followed, straightening his shoulders, trying to look bigger, and glanced at the older girl for approval, but she didn’t notice. Pursing her lips, she looked Malenie up and down. “Where you going, Orphan?”

The insult stung. “I don’t want to fight,” Malenie said, knowing it was the wrong thing to say even as she said it.

“She doesn’t want to fight,” mimicked the boy.

Malenie took a deep breath, letting the anger build up and push everything else aside, and screamed, “Rot you!” in the girl’s face, using the noise as a weapon. The girl flinched back, and Malenie whirled, catching a glimpse of the boy’s shocked expression, and pelted back the way she had come. She burst out of the alleyway, almost colliding with the skinny rooster of a boy who was the worst of the bullies. He flinched back and she dodged around him, rage flaming up at the sight of his four friends. Cowards. He shouted in wordless triumph and they closed in on her. Head down, she charged, as the camels did in the races, hoping they would scatter. They didn’t. Her heart pounded in her ears. The bullies’ jeers were still louder.

At the last moment she swerved, intending to slide through the gap between Rooster Boy and a house. She almost made it, but he grabbed her long, straight hair, jerking her head back. Pain seared her scalp. He stuck his foot between her ankles and tripped her. She fell, scraping palms and knees, and her attacker landed on top of her, knocking the wind out of her lungs, his grunting breath loud in her ear. The others hooted, urging him on.

Malenie elbowed him under the ribs as Nes had taught her and he rolled to avoid her. Tears burned her eyes as she wrenched her hair free and jumped to her feet, but she blinked them back. She’d never cry in front of them.

Rooster Boy and his friends crowded Malenie against the house. The boy and the girl from the alley jostled for space in the tight circle around her, but otherwise the street was empty. As usual, adults were never around when she needed them.

She glared at Rooster Boy, hoping he saw only her anger. His tightly curled hair, sculpted into a crest, bobbed each time he moved. “Where you going, Red?” he sneered, without getting too close, yet. She had taught him that caution in past fights, but that had been one on one, or two or three, never seven.

To cover her fear, she showed him the back of her hand, fingers pointing up, an obscene gesture that said exactly what she thought of him. Rooster Boy cursed her, fists clenched, looked at his friends to see if they were laughing at him and caught sight of one of the half-wild dogs that scavenged for food in Trader Town. He narrowed his eyes and Malenie’s stomach flipped over. She knew that look.

“Hey, you ever notice Red here is the same color as the dogs?” His friends nodded energetically. Their skin was brown-brown, black-brown or gold-brown; in Trader Town only Malenie and her papa had an undertone of red to their brown skin. Enough travelers passed through that Malenie knew she wasn’t a freak because of the color of her skin, but that didn’t matter to them. She was different, and that was enough.

“Are you a dog, Red?”

“Do you eat trash, Red?”

“Hey, when are the slave takers coming for you?”

“Is that what happened to your Ma, doggie?”

“Shut up!” She jumped at Rooster Boy, fists swinging, and clocked him in the mouth. He fell back, howling, and she darted through the opening he gave her, stretching into a run, her knuckles stinging.

“Get that little dog!” Rooster Boy yelled. “I’m going to grind her face in the dirt.”

Malenie ran faster. They’d done it before, but they weren’t going to catch her again today. She raced down two more deserted streets and across the dusty north-south road, jumped over the empty irrigation ditch and startled a flock of chickens scratching in the long grass under the fruit trees. The Wall that bordered the eastern edge of Trader Town beckoned. Malenie didn’t slow until its shadow touched her, and she smacked into it with enough force to rock her head back and bruise her forearms. It didn’t matter. She was safe.

Since her friend Nes had started ignoring her, the Wall was Malenie’s only refuge. The mica studding its surface flashed in the sunlight and drew her eyes, but no one else’s. The townspeople never went close or touched it. Although it was only the height of two men, no one climbed it to find what lay on the other side. Whenever Malenie had tried, dizziness loosened her fingers and she fell.

Propped against the massive, rough blocks a shade paler than the gravelly dun desert, she waited for her heart to slow. The bullies ran past on the road in a cloud of dust, still shouting “little dog, little doggie!” They sounded muffled and far away even though she could have pitched a rock and hit them easily. Their eyes slid away from the Wall and Malenie in its shadow, looking anywhere but directly at it. She patted the stones as she would a friend and heaved a breath of relief as the bullies turned back into town and their shouts grew fainter.

“You’re the dogs, except that’s an insult to dogs everywhere,” she muttered. “Go fight each other and leave me alone for a while.” She pressed the back of her neck against the cool stones and the sick tension of the chase drained away, though a different anxiety replaced it. She pulled her cuffs past her wrists, inspected her indigo sleeves for rips, straightened her collar and twitched the legs of her trousers into place.

It was bad enough she was motherless, friendless and a Parthavian, with a physician for a father in a town full of Thessem guards and bandits, but if anyone ever saw Malenie’s real secret, she’d never, ever have a hope of fitting in or having any friends.

Last she squeezed the bag at her throat. Meant to hold small coins, it also protected a gold chain that had belonged to her mama. Moons ago Malenie had slipped it out of the cedar box that held Papa’s keepsakes and sewn it into the seam. It was the one thing she couldn’t lose, the one thing neither Papa nor she herself would forgive losing. Especially since he didn’t know she had it. Malenie wiped the sweat from her forehead, wishing she could wipe the bullies’ insults away as easily. At least I didn’t have to fight this time. Thinking about it didn’t change anything and she still had to buy lunch for Papa.

Trailing her hand over the uneven stone and the fuzzy green vines clinging to it in places, Malenie followed the Wall to the market. Papa said the the north-south trade route and the western road met here because of the wide pools of fresh water spreading out from beneath the Wall. Eventually the meeting place had become a market and then Trader Town.

Malenie crouched to slurp water cold enough to make her teeth ache and then reluctantly turned to the marketplace. Travelers and residents thronged the narrow paths, carefully not stepping on the wares displayed on the sun-bleached squares of fabric on the ground. Malenie’s slow scan didn’t pick out any lurking bullies, so with a last pat to the Wall, she stepped out of its shadow. Suddenly she was noticed again; a neighbor shouted a greeting, a peddler shoved a packet of bone needles under her nose and a dog sniffed at her shins. She ducked under the edge of an orange awning that was flapping loose and found Steph, a big dark woman with dozens of thin braids wrapped around her head.

Steph relieved her two almost-grown sons of their trays of fresh pies and sent them for more with an affectionate swat. “Don’t dally, now,” Steph called after them.

Malenie’s stomach rumbled at the smell of bread, pork sausage and cumin. “Steph, two, please,” Malenie said to her back. “And good afternoon,” she tacked on for politeness.

“As always.” Steph’s usual smile turned into a frown when she looked at Malenie. “You’re late. And dusty.” She dropped a pie, which broke on the counter, pulled out a wet rag and swiped at Melenie’s face. Malenie ducked but took the rag. It was warm on her face and smelled slightly of lemons.

“If those were my kids, I’d give them a beating they’d not forget. No,” she said over Malenie’s stutters, “don’t lie and say they weren’t chasing you again today. Just because some people prefer to close their eyes and pretend they don’t see, doesn’t mean I do. Your pa is a sun-addled fool, even if his healing is the best thing to happen to this town. I don’t know what he’s thinking.”

“I don’t want him to worry.” Avoiding Steph’s eyes, Malenie folded the rag and put it on the counter.

“It’s his job to worry.” She shook a callused finger in Malenie’s face. “No more ‘Please, Steph, I’ll handle it.’ You need to learn how to ask for help sometimes. Everyone does. But since you won’t, I’m talking to your pa tonight. Now that Nes isn’t…” Steph pressed her lips together angrily. “Filthy slavers,” she muttered. “Anyways, I owe your pa for saving my littlest. Not telling him what I see is no way to pay him back.”

“Yes’m.” Malenie shut her mouth on her protests. There was no stopping Steph once she dragged in her baby’s health and the debt she felt she owed Papa, never mind she had paid in good coin. Dread churned Malenie’s stomach and she hunted for a topic to distract both of them. “So, uh, what’s new?”

Steph fixed Malenie with a stern glare. “This is not the end of it. But, since you asked, and it might cheer us both up, Salla’s goat birthed twins and a few doomsayers proclaimed it an omen. Salla just laughed and said she got two for the price of one, and didn’t she deserve some luck?” Her voice lightened as she rattled on and started to enjoy her gossip. “Remember how that boy broke the tannery’s spell stone?”

Malenie wasn’t likely to forget since it was Rooster Boy. The others had mostly left her alone while he worked off the cost. All of her muscles tightened at the thought of evading him day after day while delivering Papa’s medicines.

Steph was saying, “The stone shaper still hasn’t figured out how that boy broke the spell stone. But the shaper fixed up a new one to sniff up the fumes finally, and that’s a blessing for all of us on the north side.” She pushed aside the broken pie and rested her elbows on her counter to impart the last bit of news. “A runner came in last night. No matter what else you say of that Gravin, he always lets me know when my husband is coming home from a job. The caravan’s expected to arrive late this afternoon. Eight moons Jak’s been gone, past Pashtin, all the way to the Outer Cities.” She deftly slid two hot pies into a basket Malenie was expected to return and tapped her on the hand. “You wait for my oldest to walk you home. He’ll be back quicker than a goat can eat a burlap bag, and then you and your Papa can enjoy your lunch.”

◊◊◊

Papa looked up absently as Malenie walked through the doorway and blocked the main source of light in their little house. He had a smudge of soot across one cheekbone, but his white turban was elegantly wrapped and pristine, a sure sign he hadn’t had any emergencies today. “Lunch already?” He set aside the mortar full of astringent-smelling heartcure and wiped his long elegant fingers clean on a scrap of old tunic.

“It’s late, Papa, didn’t you notice?” She set the basket down and kissed his cheek. “Did you make enough medicines to dose the whole town?”

He checked the shadows in the yard, which were already stretched and long. “Two days without emergencies is a gift from the seven hundred gods and goddesses that I couldn’t neglect.” He stretched his back and teased, “And no one in this house has ever been late, or even forgotten to buy our lunch altogether.”

“And someone else in this house will never let me forget it,” she said affectionately, “even though I never forget to deliver the medicines.” The thick mud walls kept out most of the heat, and Malenie peeled her tunic from her skin, flapping it to funnel some of the cooler air under it. “I know how finicky the—”

“What’s this?” He touched her shoulder, his fingers slightly sticky on her skin. Craning her neck, she spotted a short tear in the seam.

“I didn’t know it was there. I’ll fix it.” Escaping the sudden sharpness of his regard, Malenie closed the curtain across the alcove where she slept and changed into her spare tunic. Usually he reserved that look for his patients. When she emerged, Papa took the ripped one from her without a word and mended it with quick, neat stitches. She could have done it, but it made her feel safe, in a way she couldn’t explain, to have him do it with the same meticulousness he used to set bones, wrap bandages and tap the healing drum.

Papa said, “Malenie, you have to—”

“—be careful,” she finished. “I know.” She busied herself washing her hands and then moving his books. Like many of the things in their one-room house, the table had been offered in payment for Papa’s services by a grateful merchant. The thought of replacing their rope-strung table with a ‘proper’ one of solid wood had pleased Papa so much he hadn’t been able to refuse, even though it was worth far more than the healing.

As they ate the spicy pies, Papa relaxed enough to ask about her day. She repeated Steph’s gossip but not her intention to visit. “Gravin’s caravan is arriving soon. I’m going to watch it come in.”

Papa finished chewing and frowned at her. “I hope you know enough to stay away from Gravin,” he warned. “He’s a dangerous man.”

“I don’t care about him,” Malenie said, tossing her hair back. “I want to see his caravan. They’re always the biggest.”

“There’s a reason for that.” Papa put down his lunch. Usually he was a little vague, almost always thinking about several things at once. Now all his attention was focused on Malenie again and it made her squirm.

“Papa, everyone knows he’s a bandit, as well as a merchant.”

“Just because half the men in this town are sometimes bandits doesn’t make it right. They kill and rob Gravin’s rivals to make him richer. He wants to be an important man, with all of the privileges and none of the duties.” The lines around his mouth deepened and he pushed aside the scraps of his pie. “And there are rumors he’s involved with the slavers.”

“Papa—”

“I won’t stop you from watching the caravan come in, but be careful. No, be smart. And keep your sleeves down.” Malenie bit her tongue to keep from mouthing the last words along with him. Instead she gave him a peck on the cheek and dashed outside.

Nes, Nes’s sibs and their goat were in their yard next door, so Malenie swung on the gate and waved, hoping this time Nes would acknowledge her. Nes had changed when her pa left, gotten surlier and closed off. After her cousins were taken by slavers and her aunt and uncle went looking for them and never came back, she had thrown herself into helping her ma, making soap, taking in the neighbors’ wash and caring for her sibs. She stopped talking to Malenie. Malenie had cried her confusion to Papa, who counseled patience, saying everyone dealt with grief in a different way.

Days and moons passed, and Nes stayed away. The bullies had started heckling Malenie, then throwing things and finally closing in for real trouble when Nes didn’t come to her defense. They cornered her not too far from home and Malenie was getting ready to give up pride and scream when Nes appeared. She knocked the biggest bully to the ground with one hard blow to his head and the rest scattered. Then, without saying much, she taught Malenie every dirty trick she had learned from her pa, how to hit and how to break holds. Every day they met behind the tannery at the edge of town to practice, their eyes watering and burning from the smells that were too powerful even for the spell stones to sniff up entirely. On the eleventh day Nes didn’t show up, or any day after that. Malenie went back for ten more days, hoping, but that was the last time Nes spoke to her.

She knew Nes must be worn-out-exhausted with work and a huge ache inside, much bigger than the emptiness Malenie felt for the mother who’d died when she was born. Emptiness like that could swallow you, and because of it Malenie hadn’t stopped trying to be Nes’s friend.

Nes’s youngest sister waved to Malenie over the goat’s back, but the older ones copied Nes and ignored her. Malenie watched them for another moment, pushing down the hurt, before walking away, swinging her arms to show she didn’t care.

She beat the caravan to the center of town, but not the rumors that it had been sighted. Standing on the low wall that separated the pools from the dirt of the market square didn’t give her the best view, especially as peddlers and shoppers crowded against her, but with the water at her back, no one could sneak up on her. The kids that jumped up next to her ignored her, but out of excitement, not meanness.

“It’s here, it’s here,” one squealed.

“Twenty-five camels,” the merchant in front of her counted. Malenie leaned to the side to see around him.

“That’s not possible,” his companion said. “How’d he manage? The longest train I ever saw was fifteen and I heard they bribed the bandits with half their goods to let them pass without bloodshed.”

Camels bawled and the crowd rippled to accommodate the arriving caravan. The two men were jostled away from Malenie’s perch, and she caught glimpses of dusty guards, a robed pilgrim, and camels and horses, which were an exciting change from goats, dogs and pigs. She pushed up on her tiptoes and gasped. One of the horses carried a rider with reddish skin, a pointy nose and a turban just like Papa’s. Malenie gawked until Steph’s husband Jak stepped in front of her and blocked her view. His black fighters’ braids had come loose from the nape of his neck and brushed his shoulders. Pale scars marred his leather vest, which had been new when he left.

“Jak, who’s that Parthavian?” she demanded. She and Papa were the only Parthavians living in Trader Town, though there were more, in real cities like Pashtin, where the first Family was even Parthavian, or in the far away Outer Cities. “And why aren’t you saying hello to Steph first? The line for your wages is over there.”

“Eh, now, that’s a nice hello,” Jak rumbled. He frowned down at her, solid and solemn. He never changed, no matter how far he walked away before walking back. “Since you asked, I came looking for you with a warning. That Parthavian is a mean one, so don’t be catching his attention. If he sees you, he’ll be noticing you—you’re like a wee red chick in a flock of brown ones.” He tweaked her nose, just like he’d done since she was little.

Malenie batted his hand away too late and pretended to glare at him. “I’m not so wee any more.”

“Promise,” he said.

“I do.” She sighed and stepped down out of sight. “Will you tell me about your trip later?” she asked instead of the hundreds of questions he’d provoked.

“Of course.” The crowd parted around him and then closed back up as he waded away, leaving Malenie with a fine view of a bunch of backs.

“Well, this is useless,” Malenie said and slipped behind a few loaded camels as they were led away. Half the town would be betting against the other half on what was in the odd-shaped bundles. She tried to guess the cargo by its shape. It didn’t smell of cinnamon or cardamom and it was the wrong shape for bolts of silk, linen or cotton. Once Gravin had brought a whole caravan of spell stones to punish their local shaper for something. The shaper had lived off clandestine charity for two years while Gravin sold spell stones at inflated prices, and everyone bought them, they were that scared of him. But the bundles didn’t look right for spell stones, and there was an odd sharp smell she couldn’t identify.

Down a side street, Malenie glimpsed the Parthavian man again, head bent as he spoke to the stranger who had exclaimed over the number of camels in the caravan. She scudded past, and they never looked around. At the open ground between Trader Town and Gravin’s compound, where she had no way to remain unseen, she gave up and turned for home. The shadows stretched long and the sun was low and red in the sky. In town, poor man’s lanterns—tiny flakes of rock like mica that drifted on the wind and were collected by the poor—flickered to life on lintels and along rooflines. The occasional lightcrystal, made by a shaper, shone brightly from a wealthier house. Although Malenie was hot and thirsty, the thought of Steph telling Papa exactly how badly Malenie was taking care of herself slowed her steps.

Some links are affiliate links which means I earn a small commission without any cost to you, which helps support me while I write more books.